Historical Timeline

- 1820s to 1840s

- 1850s

- 1860s

- 1870s to 1890s

- 1900s – 1940s

Cadia, 1862-1864 – Josiah Holman, Cornish Mine Captain

John Christoe himself may have informed Robert Morehead that his expertise lay in smelting, rather than exploration and mining. Morehead therefore had to make two important decisions in early 1862. The Cornish beam engine, manufactured in 1859 in Cornwall at a cost of £1,225, had been landed in Sydney in 1860. It was originally intended for the Good Hope Mine at Yass, but Morehead had delayed in the expense of transport. He now decided to transport it to the Cadiangullong Mine, where it would soon be needed.

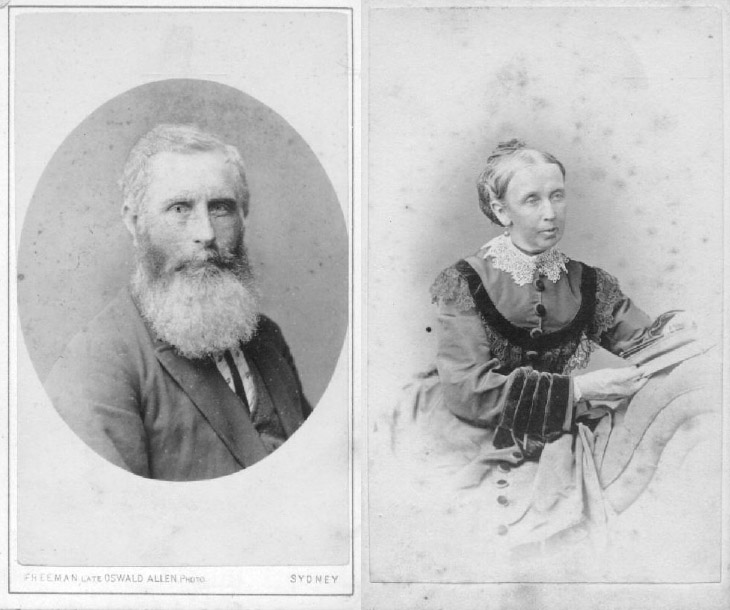

In addition, he procured the services of Josiah Holman, who arrived to take over the operation of the mine in March 1862. Holman was widely experienced in Cornish deep mining and his services would allow Christoe to concentrate on the management of the smelting operations.

Holman was born on 27 September 1821 at Gwennap, Cornwall, the son of James Holman, mining engineer, and Grace Trenwith. He began work as a miner at 14 years old and trained as an engineer. He married Elizabeth Simmons at Gwennap in 1841. He became highly skilled in mining practice and became a mine captain operating in Brazil, the Philippines, Canada, North America, South Africa and Malacca. His children, Elizabeth, John Henry, Emily, Josiah, Charles and Annie were born in a variety of different countries as a result.

He settled in New Zealand in 1859, resolved to becoming a farmer, if no other opportunities arose. His daughter, Annie, was born there in 1859.

Josiah Holman knew of John Penrose Christoe through his brother, William Henry Christoe, who was an assay master, based in Truro, Cornwall. Josiah wrote to Christoe to seek any opportunities and John wrote in reply in 1862, with an offer of appointment as mine captain at Cadia. Holman accepted and arrived in Sydney in March 1862 to take up the post. Though Holman gave up his farming ambitions in New Zealand, he was to later amass a large acreage of land around the Cadia mine in his own name.

Of all the people who came to Cadia, Josiah Holman was the one who stayed the longest, always ready to help the community whenever in need.

Within six months and by September 1862 Josiah Holman had reservations on the prospects of the Cadiangullong Mine (East Cadia). All work on the Engine House was suspended until the results of exploration were available.

By November 1862, the East Cadia Mine proved unpromising in terms of ore quality and waterlogging.

In March 1863, Robert Morehead, on the advice of Josiah Holman, suspended most operations. Christoe and Johns were blamed for the exaggerated reports of the potential of the mine in 1861. Consideration was given to writing off the capital already expended and risking legal action by forfeiting the lease.

However Holman had been exploring neighbouring deposits with the potential to keep the smelting works in operation. On 15 May 1863, Morehead finalised arrangements with the landowners for a 12 month trial period including the former Canoblas Mine and also the west bank of Cadiangullong Creek (West Cadia).

The 12 month trial of 1863 and 1864 proved the prospects of the West Cadia properties, but also resulted in the decision to abandon the Canoblas Mine.

The evidence suggests that East Cadia (the Cadiangullong Mine) was the original site for the engine house. It certainly could not have been at West Cadia in 1862, as no exploratory work had been undertaken there until 1863 and 1864.

While Christoe and Holman now jointly provided all the required expertise to run the copper mine under the watchful eye of Robert Morehead, to make a success of the venture it would nonetheless be necessary to tap into the resources of the many other Cornishmen, who had been forced to migrate around the world to seek mining employment – the Cornish Diaspora.

The reappraisal of the potential of the copper deposits at Cadia by Josiah Holman had a profound impact on the future of the mine and its ownership.

The Cadia Engine House in 2003, after conservation works (scale 1 metre) (Edward Higginbotham, 2003).